PUBLIC RELATIONS

Tuesday 22nd January 2019

Book review: Rethinking Reputational Risk, by Anthony Fitzsimmons & Derek Atkins

That people suspect Facebook of being involved, and that the rumour went viral, is indicative of the suspicion with which the company is held by since its flaccid approach to privacy became widespread public knowledge.

These suspicions are not new. There was the row over Facebook’s Beacon user-tracking service in 2007, concerns about facial recognition, a bungled psychological experiment into the moods of its users, and run-ins with the US FTU, ACLU and privacy commissioners in multiple jursidictions over many years.

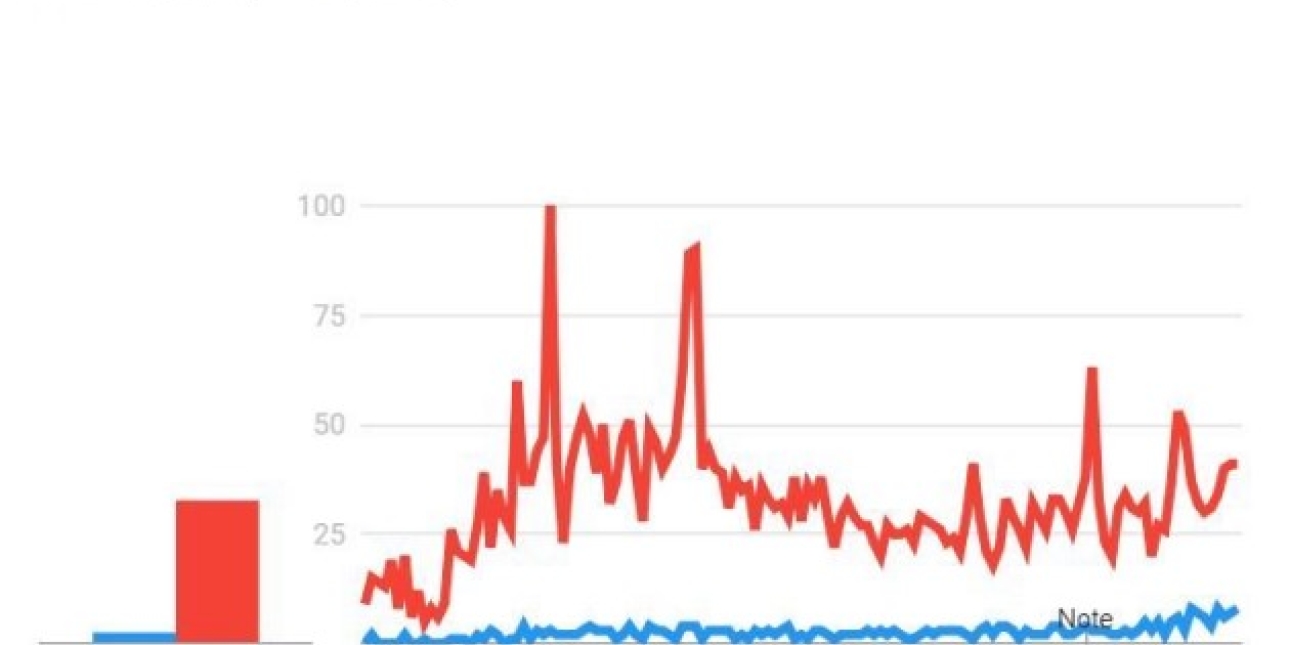

Unsurpisingly, according to Google, there has been considerable public interest in privacy (mostly as a proxy for internet and/or data privacy) for many years.

Given The Guardian’s initial story in December 2015 about the covert harvesting of user data by Cambridge Analytica did not ignite until whistle-blower Christopher Wylie lifted the lid on Cambridge Analytica twenty-six months later, Facebook had plenty of time to tackle the problem and prepare a meaningful response.

Yet they did little to address the core of the privacy issue, Mark Zuckerberg disappeared as soon as the story ran, and Facebook’s value dropped USD 119 billion in a single day. Zuckerberg hardly helped matters by refusing to appear before the UK DCMS Enquiry into Disinformation and ‘Fake News’.

How did Facebook fail to anticipate a major privacy crisis when the writing had been on the wall for so long? Were its leaders truly ignorant and out of touch, or simply failed to act substantively on the many warning signs? Why did they behave the way they did? Was Facebook’s experience isolated, or consistent with other reputational meltdowns?

These are the kinds of questions posed by lawyer Anthony Fitzsimmons and insurance expert Derek Atkins in their book Rethinking Reputational Risk, in which they get to practical grips with the notoriously knotty, slippery topic of reputation risk management.

Drawing on analysis of recent high profile crises such as BP’s Deepwater Horizon spill, Barclays’ LIBOR rigging, Tesco’s false accounting, and the VW diesel emissions scandal, the authors argue that the problem lies in the complexity of many modern businesses, the emergence of multiple online ‘unseen systems’, fast-changing stakeholder behaviours, inadequate listening, issues management and crisis preparedness, and an unwillingness to get to the root problem of problems and failures, chiefly due to over-confidence, complacency and hubris.

All this sounds familiar. But the book comes into its own when it addresses the failure of ‘classical’ risk management and the three/four line of defence model, which is regarded as overly rigid and ill-suited to handling the many and varied behavioural risks, from weak culture and values and inappropriate incentive schemes, to the blurring of personal and professional lives and the character and personality traits of senior leaders.

The authors rightly argue that reputation risk is first and foremost a leadership responsibility, and too often it is at Board level that things fall down. Board failures were involved in 50% of the 42 crises studied. Why? As Boards are essentially self-selecting, and overly reliant on people with financial and operational experience, as opposed to the forensic, analytical, behavioural and digital skills that are required in today’s globalised, networked and inherently volatile economies. There is much in this.

Since concerns about Facebook’s approach to privacy first started emerging several years before its murky dealings with Cambridge Analytica came to light, Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg have admitted that they should have taken user privacy far more seriously.

The important question on why they didn’t heed the warning signals earlier appears to have one plausible answer: user privacy was regarded as a price worth paying for growth, and they would make the most of it while the sun shone and regulators, politicians, customers and the general public had more important fish to fry.

Mark Zuckerberg may insist he is personally responsible for Facebook’s privacy lapses, but Facebook’s board is also responsible and must prove itself equal to the task of fixing the holes properly, and holding its CEO to account. Its members would do well to read Fitzsimmons and Atkins’ excellent book.

Meantime, Facebook must shoulder part of the blame for the many rumours about it – be they accurate, misinformed, or plain false.

Photo by Susan Yin on Unsplash