PUBLIC RELATIONS

Tuesday 21st August 2018

Those who can do better, advise

Everyone who’s ever arranged a party can claim some level of event management experience. Who isn’t a participant in the media now we all use social media? Doesn’t every former journalist think they could do a better job of media relations?

Our industry has plenty of doers, and many of us enjoy nothing more than making things happen and getting results.

The only problem is that low barriers to entry plus a (mistaken) sense that anyone can do the job means that entry-level salaries have stayed low in the sector. If you have no broader ambitions than to work in event management, content marketing or media relations, it’s unlikely that you can boost your earnings far unless you’re your own boss and very good at what you do.

To give an analogy from the world of medicine, nurses are in the frontline of health care provision. They are the doers. The role demands dedication and professionalism (and requires plenty of training). But, despite our gratitude for their difficult and important work, nursing does not typically bring high social status or high salaries.

These are reserved for doctors, who do less doing, but who make the important decisions: which medicines to prescribe; whether surgery is needed.

Let’s assume that everyone has some mastery of the craft of public relations (we’re all doers). We’re like nurses, responding to every call and adept at cleaning up the mess. But what’s next?

The next step is to explore not what you do, but why you do it.

This involves understanding the organisation(s) you’re working for, in the context of their business environments. It involves thinking through the role of public relations and communication alongside marketing, human resources and other functions. It involves developing strategic plans and persuading senior executives of these plans. It involves setting budgets, which in turn requires an ability to understand how to set objectives and to measure results against these objectives. It involves, in short, an ability to become a PR and comms adviser, not just a PR and comms doer. To be a doctor, rather than a nurse.

But how to make the transition from being a comms doer to becoming a trusted adviser specialising in public relations and communication?

Some will gain it through experience and opportunity. ‘Some are born great. Some achieve greatness. And some have greatness thrust upon ‘em.’

But most may need to step aside from the day job to acquire new ways of thinking and doing and to learn from best practice.

The CIPR professional qualifications have received major revamps in recent years and they’re now bedding in well (the new Professional PR Certificate has run for one full cycle; and the Professional PR Diploma for two).

These qualifications are offered by some universities and by specialist training companies such as PR Academy (face to face and distance learning options are available) - but the syllabi are no longer primarily academic. They are focused on what’s needed to make the step from doing to advising.

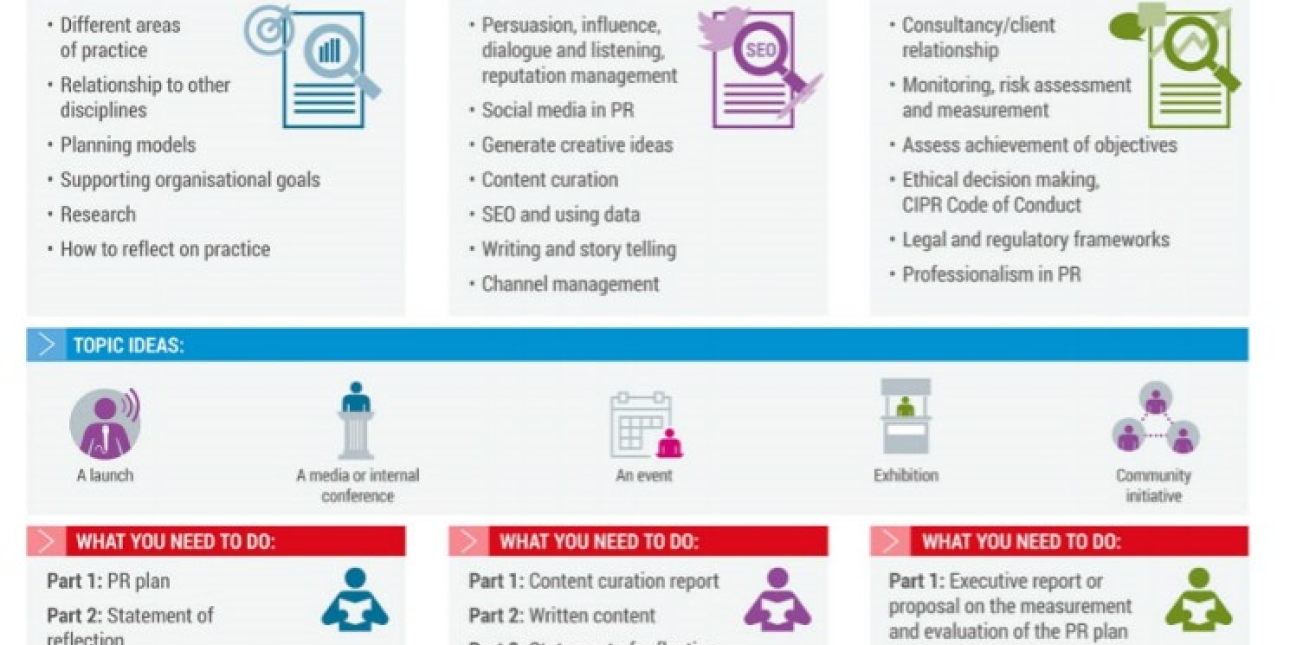

CIPR Professional PR Certificate

The CIPR Professional PR Certificate is the more junior of the two qualifications. The expectation is that candidates will be graduates or will have been working in field, at a junior level, for two years.

The first assignment requires candidates to prepare a public relations plan for a real organisation accompanied by a statement of reflection.

The second assignment focuses on delivering the plan (it’s all about writing, storytelling and SEO). The final assignment requires candidates to explain how they would evaluate the results. The assumption is that all three assignments relate to the one, real, organisation - so candidates create their own assignments.

CIPR Professional PR Diploma

The CIPR Professional PR Diploma is suitable for more experienced candidates who are ready to advance into senior management roles.

Its assessments follow the same pattern, but with the expectation of much more sophisticated outcomes. Candidates prepare a strategic proposal; they research and write a piece of thought leadership content; they write a management report recommending performance improvements within the PR and comms function. All three assignments are accompanied by a piece of reflective writing detailing the research involved in producing the proposal, the article or the report, and discussing academic and practitioner models used to develop the piece of work.

So academic concepts are present in the new qualifications, but they’re applied to the real world, not discussed in isolation as in an essay. Referencing conventions are more likely to follow business conventions (ie endnotes) than academic conventions (eg Harvard referencing).

Does this make the new qualifications easier? Yes - and no!

A high proportion of assignments meet the pass criteria, as would be expected from practitioners who are writing assignments based on their work. But the assignments are large, and completing them alongside busy working lives can be challenging.

Some find academic essays harder (you have, in effect, to learn a new way of thinking, writing and referencing) - but for others, essay questions are easier. That’s because the field of knowledge is finite, constrained by what has been published by reputatable academics.

I’ve taught and assessed both qualifications, and have generally been pleased and impressed with what has been submitted. It should come as no surprise that public relations practitioners are above-averagely literate.

But there’s one area that’s very much a work in progress. I remain disappointed that many candidates struggle to write persuasive reports and proposals. They can do the research; they can do the analysis. But not all can turn this into a management report designed to win the support of senior managers. Not all are as confident with numbers as with words.

In other words, our industry is full of people who are good at managing downwards, who can get the job done. But there’s less confidence in managing upwards - and in persuading others why the job needed doing in the first place, and where additional resources should be committed in future.

We may not all operate in the private sector. We don’t all work for public relations consultancies. But ambitious practitioners in the public and no-for-profit sectors (working internal and in external comms) should also view themselves as consultants capable of becoming trusted advisers.

Remember, it’s the doctors who command the bigger salaries, not the nurses.

At PR Place we have provided some guides and toolkits (free to registered members of this site) to help practitioners develop a more strategic approach to comms and to help CIPR professional qualification candidates to succeed. Please check them out here.

Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash

Read Original Post