Building bridges between crisis comms practice and academia

Why so often are conversations between practitioners and academics in the crisis communication space lacking?

Last week, I had the pleasure of chairing the CIPR Crisis Communications Network’s first virtual event of the year: ‘Building bridges: what can crisis communication practitioners and academics learn from each other?’

Alongside Chris Tucker (the network’s co-chair), I was joined by a panel of genuine big hitters from across the practice and academic spectrum, encompassing Audra Diers-Lawson, Professor in Strategic Communication at Kristiania University; James Barbour, Vice-President, Global Public Relations and Strategic Projects at Schneider Electric; and Jonathan Hemus, Managing Director at Insignia.

As many readers of this blog will have seen, Collins Dictionary last year made ‘Permacrisis’ their word of the year. And the fifth annual PR Week/Boston University Communications Bellwether research found “the ability to handle crises” to be the most important PR skill.

However, as our industry seeks to capitalise on the opportunities inherent in this issues-rich, risk-laden environment, there remains one conversation almost entirely missing – that between practice and academia. That is what our event was about: exploring the interaction (or lack of) between practitioners and academics in the crisis communication space.

Although the focus of the discussion was intentionally issues and crisis-specific, we inevitably touched on the underlying issue of practice/academic interaction overall, across the strategic communication and marketing communication arena.

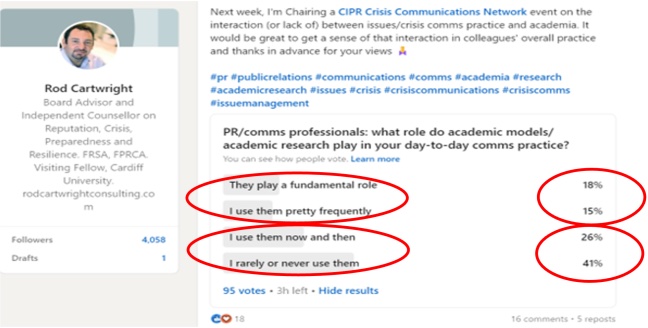

That overall challenge was highlighted by a quick poll I ran on LinkedIn to gauge the extent to which professional communicators are drawing on academic research and models in their day-to-day practice. The numbers from nearly 100 respondents speak for themselves.

So what did we find in discussing the nature, size and reasons behind any gaps between crisis communication practice and academia, the opportunities we may be missing as a result and what we can do to bridge the divide?

There is undoubtedly a cultural and attitudinal divide between academia and practice, particularly in the UK’s ‘hostile environment’ to academics. This is characterised by practitioner stereotypes that academics do not have practical experience at the coalface and academic views that practitioners lack replicable rigour in their practice.

These are compounded by structural barriers within both communities which reinforce these views. Paywalls for academic papers, the constant need for funding, long-term timescales for academic research and the inaccessibility of much academic writing run counter to practitioner integration of academic work into their practice. On the practitioner side, a short-termist ‘solve it now’ focus, an expectation of overnight answers and margin pressures all militate against greater collaboration.

There is a definitional debate to be had on what constitutes ‘academic’ research. There is no shortage of theoretical and conceptual frameworks widely developed and used in practice, with practitioners often unaware that those models actually draw on research and thinking from academic ‘seats of learning’! Debates around the ‘separation of church and state’ between academia and practice set up a false division when there is, in fact, a spectrum on which both sit.

In the absence of PR being a true profession, the sense that the communication function can be viewed as functional – rather than strategic – may limit the extent to which practitioners are able to integrate academic thinking into their work. With the best crisis preparedness (eg systematic risk assessments, scenario planning and resilience-building) being both truly strategic and business-critical, crisis communication may well be particularly well suited to greater practice/academia collaboration.

There is no quick fix to the somewhat tribal relationship which currently exists across academia and practice, with fear and misunderstanding of ‘the other’ playing a key role. However, there remains enormous potential for the building of mutually beneficial relationship-building and collaboration.

An understanding and practical recognition of the structural and practical realities faced by academics and practitioners is a crucial starting point. That understanding must also be translated into practical action, in terms of how potential collaborative engagements are approached and structured.

This is particularly true when it comes to each party having the incentives needed to make any engagement meaningful, including establishing realistic timescales on both sides, co-creating research briefs and respecting commercial realities. At the same time, recognising that the accessibility and practitioner ‘ease of use’ of research outputs is important for academics in simplifying and synthesising academic work.

Finally, hiding in plain sight was the core insight that key to breaking down barriers and building bridges is what we all do: communication, engagement and dialogue. The mere fact of having practical, structured conversations about this crucial-bridge building is a crucial starting point. Formalising such discussions in the form of ‘brains trusts’ – incorporating both practitioners and academics – provides an invaluable example of how such conversations can be translated into concrete collaboration.

As with much in life, there is no silver bullet here. However, starting in our own backyard, with greater levels of communication, dialogue and practical engagement seems like a very good place to start.

Rod Cartwright is a special advisor at the CIPR Crisis Comms Network.