What Westminster can learn from devolved governments' comms

The hard work behind good policy can easily be lost if the communications strategy is weak, reactive, or bolted on at the last minute.

As public faith in politics continues to erode, communications professionals must look beyond messaging strategies. Comparative policy learning from the UK’s devolved governments shows how strategic communications can demonstrate legitimacy and build trust.

Public engagement and political trust are in trouble, as falling voter turnout demonstrates. With new parties like Reform aiming to gain ground in the upcoming elections in Wales and Scotland, the way the nations of the UK and Ireland are governed could shift significantly. More than ever, governments need to show their working and this includes making the process behind policy decisions visible to avoid being seen as tokenistic or self-preserving.

At PolicyWISE, I work across the UK and Ireland comparing how governments develop, communicate, and deliver policy. My experience shows that the hard work behind good policy can easily be lost if the communications strategy is weak, reactive, or bolted on at the last minute.

Lesson 1: Embed communications from day one

Across the devolved nations, we’ve seen high-profile policies with strong public value which lose popularity due to mixed communications or confusion about why a policy is being enacted in certain areas and not all.

In Scotland, the introduction of minimum unit pricing (MUP) for alcohol in 2018 was a landmark public health measure. While grounded in evidence and aiming to reduce alcohol harm, early communications focused heavily on justification rather than engagement. Many people were unclear about how it would work or why it mattered to them.

In Wales, the roll out of 20mph default speed limits aimed to save lives, improve safety, and promote active travel. But backlash was swift, amplified by social media, and weaponised by political opponents. The government emphasised benefits but underestimated the emotional and identity-based resistance in some communities.

Both cases underline that policy logic is not enough. Public legitimacy depends on making people feel heard, respected, and involved from the start.

Lesson 2: Anticipate emotional responses and build alliances

Not all major policy changes face lasting resistance. Scotland’s 2006 ban on smoking in enclosed public places remains a textbook example of communications done well. The Scottish government spent months preparing the public and businesses, framing the change as a matter of fairness and health. They enlisted hospitality groups, doctors, and well-known advocates, while sharing personal stories about the harm of second-hand smoke. Likely objections, such as fears about economic damage to pubs, were addressed early with evidence from Ireland’s earlier ban.

The result? Public opinion flipped from initial resistance to majority support within months of launch. Careful preparation, coalition-building, and proactive myth-busting can transform the public acceptance of even controversial policies.

Lesson 3: Use comparative learning to rebuild trust

Devolved governments face many of the same challenges as Westminster, including public disillusionment, but often tackle them differently. That variation is valuable.

• Scotland has experimented with participatory democracy, from citizens’ assemblies to MUP implementation, offering insights into innovation and its limits.

• Wales has shown how a strategic narrative, like the Well-being of Future Generations Act, can provide a unifying framework when backed by early investment in public dialogue.

• Northern Ireland demonstrates that engagement must be part of trust-building, not a substitute for it, especially in divided contexts where credibility is everything.

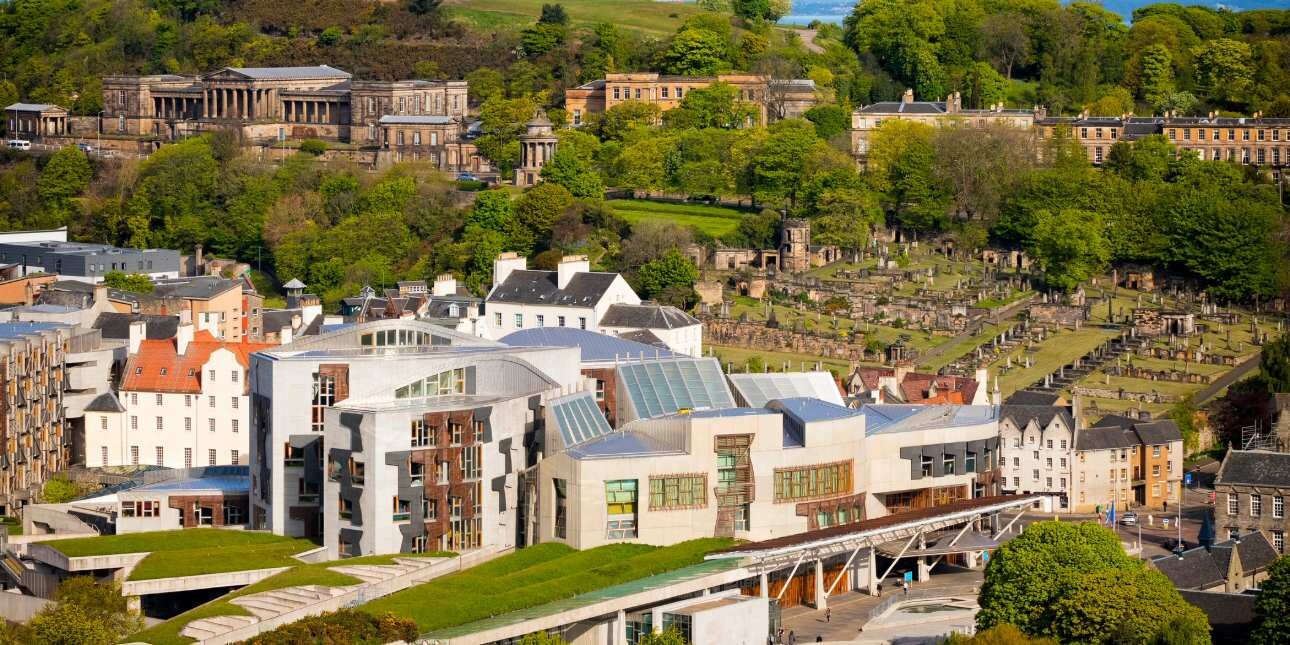

Our PolicyWISE roundtables in Edinburgh, Belfast, Manchester, and Cardiff found a consistent need for governments to shift from being devolution-aware to devolution-able, ready and able to work with different contexts, voices, and expectations.

The communicator’s role in a devolved future

Strategic communicators often work close to power. That gives us both opportunity and responsibility to shape how institutions listen, respond, and evolve. Trust isn’t a communications product. It’s built through honesty about complexity, clarity about trade-offs, accountability for results, and consistency over time.

As we approach the next devolved elections in 2026, the conditions for public trust are fragile, but they are not beyond repair. Comparative learning offers the same promise for communications as it does for policy: better outcomes if we pay attention to the lessons all around us.

Catherine May is senior external affairs and communications manager at PolicyWISE.

Further reading

How PR can navigate a fragmented UK political landscape

Book review: A Different Kind of Power by Jacinda Ardern

Why you should use LinkedIn for public affairs