Good grief: Reframing the last taboo

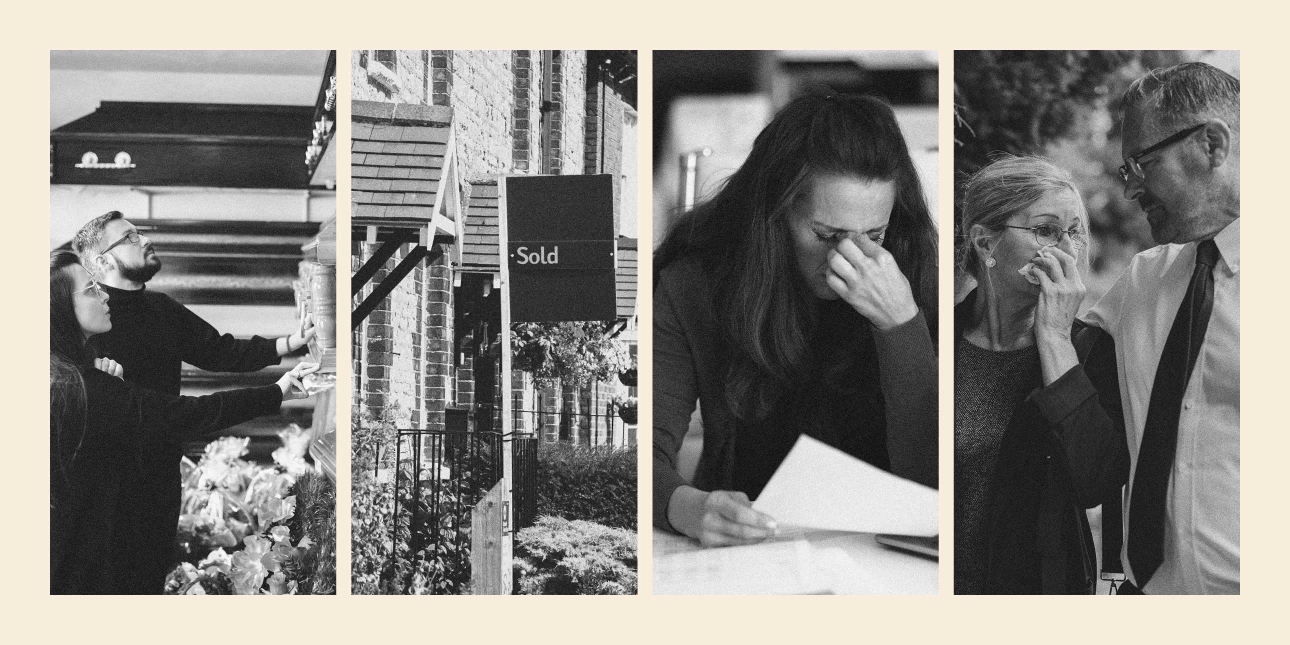

Grief – it’s awkward and difficult, traditionally treated as either something to ignore or to take two weeks off and then return to life, brave faced and stoic. But, says Kitty Finstad, grief is far messier, chaotic and destructive than that. And as attitudes and understanding of grief changes, our comms need to shift too.

Of all the members of the 21st-century Taboo Club, it’s only grief that’s still sporting its Most Awkward lapel pin. All the others have shuffled out from under the carpet of shame and let their membership lapse: sex, menopause, mental health, gender, abortion, religion, addiction… they’ve all emerged with nary a blush into a brave new world of openness, diversity and acceptance. Everyone wants to meet them, welcome them, wave the flag for them.

Not grief. It’s a proper mood killer, party pooper, energy vampire. A depressing Debbie Downer that nobody wants to be around. Not even the pointiest Victorian mourning pin can pierce its carapace of doom.

But… as the whole world picks their way through the collective web of grief brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic, things may actually be looking up. And while there’s no magic formula for coming to terms with or ‘getting over’ grief, we may finally, slowly be getting better at preparing for it, supporting each other through it (even welcoming it) and talking about it.

Even for PR and comms professionals used to dealing with crisis messaging, death remains a touchy subject.

While we can grieve the loss of everything from a relationship to a job we loved to ‘the good old days’, it’s death and bereavement that hoard the lion’s share of grief. And despite death’s pervasiveness and unavoidability, we still tend to avoid talking about it, especially in Western societies, where end-of-life largely remains a private, behind-closed-doors event. Even for PR and comms professionals used to dealing with crisis messaging, death remains a touchy subject.

In November 2020, a poll commissioned by the UK cancer charity Sue Ryder found that 24 per cent of employees – which extrapolates to around 7.9 million UK workers – had experienced bereavement in the previous 12 months. The knock-on economic costs caused by absences and decreased productivity were estimated at £23bn a year. That’s a lot of grieving colleagues and a lot of tissues.

FACING FEARS

Author, journalist and funeral celebrant Lorraine Wilson believes the stigma attached to talking about death is down simply to one thing: fear of the unknown. “When someone dies, it reminds us of our own mortality – and with that comes fear, whether you’ve been raised in a way to believe there’s something after life or not.” Confronting that fear with knowledge is a good start.

Counter to some commonly held beliefs about the ‘five stages of grief’ described in the 1960s by Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, grief doesn’t follow a neat step-by-step, beginning-middle-end process. In fact, Kübler-Ross actually ascribed those five stages – denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance – to the dying person. Over the decades, we’ve somehow adopted them as the domain of the bereaved, perhaps in order to try to make sense of the mess of confusion and jumbled emotions that accompany grief.

And there’s an awful lot most people don’t know when it comes to loss and mourning. It’s not that the information doesn’t exist, it’s that fear prevents us from seeking it out until we have no choice – and often at the same moments that the bereaved are deep in a quagmire of painful grief.

For Natalia Pazzaglia, the pain of losing her mother to cancer came with a severe financial shock too. “Talking about money is almost as taboo as talking about death,” she says. To be with her mother in hospital in 2016, Pazzaglia had to work remotely. “This is when no one was working remotely. I had to make financial choices about the type of work I could do that would allow me that freedom to be with my mother when she needed me.”

But that wasn’t the only financial hurdle she encountered. There was the shock of the cost involved in settling her mother’s estate. Not knowing where to start was her biggest challenge. “Eventually I found out that I needed to talk to all these professionals: property managers, people to help me sell the house, a probate lawyer, a tax accountant. When I approached them and asked for costs, they each gave me a range of between £2k and £8k. Multiply this by three and that could be between £6k and £24k. A huge difference. I hadn’t planned for this and because I didn’t know how much money the whole thing would end up costing, I just didn’t know what to do.”

Pazzaglia has used her own experience to found the start-up Legacy Compass, a platform that helps people to create a digital home for their memories, life stories and personal wishes, as well as the facility to create a family-shared repository for essential information and documents. It's an all-in-one tool that enables individuals to easily share invaluable memories alongside planning and making preparations for their own death.

Now in early-stage fundraising, the tool will guide users through storytelling paths based on more than 70 user interviews over two years of development which began with the tech-for-good platform Lasae, launched in Italy by Pazzaglia in 2022. As a natural storyteller, Pazzaglia believes in the power of conveying authentic experiences and of encouraging transparency. “What came out from the interviews is that speaking about death is still a big problem for a lot of people. Culturally, we don’t want to go there.”

CULTURE CHANGE

But go there we must. And there are indications that the examination and depiction of grief is becoming not exactly mainstream but certainly more visible. Fans of Sex and the City who tuned in to its 2020s incarnation, And Just Like That, watched Carrie Bradshaw (Sarah Jessica Parker) witness the death of her beloved Mr Big in the first episode. For the rest of the season, Carrie’s grief became another virtual character. Likewise in the pilot episode of the 2023 series The Bear, the main character’s is tortured by his brother’s suicide; his grief appears as a caged angry bear in his dreams.

These dramatised manifestations of grief are useful in helping to raise its veil, paving the way for authentic, relatable storytelling.

These dramatised manifestations of grief are useful in helping to raise its veil, paving the way for authentic, relatable storytelling. That’s what marketer and podcaster Heather Pownall wants to achieve with her podcast, Everything Has Changed: A Weirdly Uplifting Podcast About Grief [season one scheduled for release spring 2024]. Together with her friend and ‘partner-in-grief’ Hilary, Pownall wants to open up the conversation around grief and loss, with the aim of helping others.

“Our motivation for doing the podcast was to impart knowledge, partly through sharing our experiences of each losing a parent in late 2021, but also through bringing in experts to demystify or educate on particular topics around death and grieving so people can take away what they need. There are so many aspects of grief and we’re starting from one particular base point [adult child losing a parent] that’s highly personal to us, and also a huge part of healing and supporting each other.”

During the production of the podcast, Pownall and her team will release a series of newsletters to document and support the themes of each episode, which include “What I Wish I Knew”, “Patient Agency”, “What Hope Looks Like”, “Culture and Rituals”. As a collection, the series should, says Pownall, form a sort of toolkit for healing, with branding that’s purposefully light, colourful and approachable, unscary.

Lorraine Wilson observes that some language and terminology around our ultimate ends still has the power to cause extreme discomfort to the bereaved. “Some people find it uncomfortable to hear that a person has ‘died’ – they prefer ‘passed’. In my role as celebrant, I usually say ‘Will you please stand for the committal.’ At a recent ceremony, one elderly lady had warned me ahead of time that she hates the word ‘committal’ – going in the ground. So we agreed that I would instead say ‘prepare for his final journey’. That made her feel more comfortable on the day. You have to be an empath in this job and adapt to the expectations of the bereaved. Ultimately, the family is channelling through me what they want to say and hear about their loved one.”

Making sure relevant, tonally appropriate resources are accessible and answering the right questions is key.

Making sure relevant, tonally appropriate resources are accessible and answering the right questions is key for service providers, whether that’s grief counselling or choosing a casket. Ciarán O’Toole, CTO and former Director of Product & Innovation at funeral provider Golden Charter, emphasises the importance of offering quality content to suit different scenarios. “The way people talk about their inevitable end differs from person to person. Some embrace it, others avoid it. So we have a whole range of blogs on our site that answer some of most commonly searched terms online, such as “what to do when someone dies” and “how to register a death”.

These blog posts are part of a long-term marketing strategy for the business that, says O’Toole, “continues to have a very positive impact on our customers seeking support and our online visibility.” Content marketing has been a principal strategy for O’Toole’s other business, localfuneral.co.uk, a service for people in immediate need with no plan. “It connects them with an independent funeral director, who guides them through the arrangements and then gives advice on bereavement support and, if needed, how to connect with a grief counsellor.”

These kinds of resources, alongside discussion groups such as Death Café (deathcafe.com) and training resources like Coffin Club (coffinclub.co.uk) go a long way to helping people towards greater awareness and acceptance. One positive takeaway from the pandemic, says Natalia Pazzaglia, is what she sees as a growing acceptance that “it’s okay to not be okay.”

“My view on grief,” says Ciarán O’Toole, is that in the UK we still have a long way to go, culturally, to open up about it and realise there are ways to engage with and manage it. While it is personal to us all, we don’t have to go on the journey alone.”